Behavioral finance uses psychological insights to inform financial theory. Behavioral finance holds that we do not behave like the rational and self-interested agent of economic theories. Homo Sapiens is not Homo Economicus. We have emotions. We are influenced by the others. We have cognitive bias. This papers aims to help you better understand how these psychological factors affect your financial decisions under risk.

Understanding the cognitive mechanism of financial decisions

Daniel Kahneman, one of the most influential figures of behavioral finance, developed the powerful “two systems of the mind: System 1, System 2” framework to describe our decision-making process.

- System 1: Intuitive, fast and effortless. We use this system when performing automatic tasks such as driving or calculating 2+2. These automatic tasks can be however complex. A business angel may have a gut feeling for a start-up after a 1-minute pitch. An art expert can recognize in a fraction of a second the author of a masterpiece. System 1 uses shortcuts, heuristics, and automatisms rather than deliberation. This is a powerful tool to make quick decisions in a complex environment. That is the reason why most of our decisions are made by System 1.

- System 2: Deliberate, slow and effortful. We use this system while solving analytically complex problems such as multiplying 47*89. Even if we can be quick, we are aware of the reasoning we use to solve the problem. We can explain and debate it.

However, they are prone to cognitive bias.

What is cognitive bias?

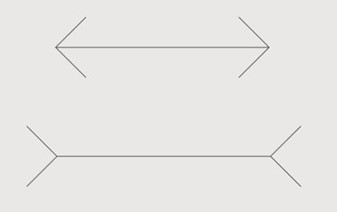

Which stick is the longest?

Have a careful look! Measure them! This may be not the one you think…

Optical illusion is an example of cognitive bias. Have a look again…you may still feel that the second stick is the longest, even if rationally you know they are the same length. Similarly, we often unconsciously use mental shortcuts to make quick decisions. These rules work well under most circumstances, but they can lead to systematic deviations from logic or reality. These deviations are called cognitive biases. Like optical illusions, even when we know we have a bias, it is not always easy to avoid being influenced by it.

| Bias | Description |

| Home Bias | Preference for domestic equities even when it is not profitable. |

| Disposition effect | Tendency to keep losing assets and sell winning assets. |

| Herding effect | Imitation of other’s behaviors. This can lead to market bubbles and overreaction to market changes. |

| Over-confidence | Overestimation of one’s skills and judgments. |

| Availability heuristics | Overestimation of the likelihood of familiar, recent or emotionally charged events. |

| Denomination effect | The tendency to spend more money when it is denominated in small amounts rather than large amounts. |

| Gambler’s fallacy | The tendency to think that future probabilities are altered by past events, when they are unchanged. The fallacy arises from an erroneous conceptualization of the law of large numbers. For example, “I’ve flipped heads with this coin five times consecutively, so the chance of tails coming out on the sixth flip is much greater than heads.” |

There are tons of cognitive biases. The table displays some common cognitive biases in financial decisions

Decision under risk: Greed, Fear and Pessimism

Let’s imagine you can invest in a bet with a 50% chance of getting either $100 or $0. How much are you willing to pay for this bet?

One investment strategy is to calculate the expected value (EV) of the bet and invest only if the EV is greater than the price of the bet. Most of us however are risk-averse and are willing to gamble only if the EV is greater than $50.

Moreover, the higher the outcome, the less sensitive we become to an outcome increase. Getting a $10 free gift coupon is a big deal. But winning $11k at casino instead of $10k may not make you so much happier… To account for this first psychological parameter, we can say that the utility we attribute to financial gains is often concave. We are rarely greedy. Instead we underestimate gains and our marginal utility is diminishing.

Now, what if I asked you to choose between paying $50, and placing a bet where you have 50% chance of paying either $100 or nothing? In this case, most of us prefer to gamble. There is some hope not to lose. We try our chances. Even for $25, we may be ready to gamble. Most of us are afraid of losing. On average, we are twice more sensitive to losses than to gains. Moreover, we are much more sensitive to a change in small losses than in big losses. If you expected to pay $10 for your meal and get a $20 bill, you may become terribly upset. But if you finally buy your house $1.1M instead of $1M, it may not really matter. In a nutshell, our valuation of losses is often convex. Loss aversion is one of the most fundamental heuristics in our financial decisions.

We are also more or less optimistic or confident in our financial decisions. If you drive a car for the first time and are told that 1M+ people die each year on the road, you may be quite scared and overestimate the probability of crashing. If you are an experienced driver, you may on the contrary be overconfident and underestimate the risk.

Prospect Theory is a decision-making model under risk which includes these psychological factors. Developed by the Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979, Prospect Theory is at the heart of behavioral finance (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Wakker, 2011).

Neuroprofiler’s algorithm assesses the parameters of the Prospect Theory utility function through an adaptive questionnaire. The objective is to better understand the client’s risk preferences and biases in order to offer him the most suitable services and products.

I’m biased…is it serious?

The basics of behavioral finance are that we do not behave like the rational and self-interested agent of classical finance. Our decisions are strongly influenced by emotions, social pressure, and cognitive fallacies. We prefer to use heuristics than deliberation. Such mental shortcuts are often presented as “bad things” which prevent us from rationality. However, heuristics is a wide term which covers many different cognitive mechanisms. Even what we mean by rationality is not always clear. Is it a deviation from individual profit maximization? From logics? From wisdom? From reality? From evolutionary optimum?

For some bias, like logical fallacies, such as base rate fallacy (ignoring prior when calculating conditional probabilities), the answer is quite straightforward. They lead to mathematical error and we’d better get rid of them.

For others, the answer is more complicated.

Let’s consider the question of risk-taking. Risk-taking behavior depends on loss aversion, sensitivity to gains and optimism. In other words, it depends on how much risk we are willing to take to win more, to lose less and how we perceive the probabilities of outcomes. Loss aversion and sensibility to gains are more a question of preference. You refuse to bet with your friend because, even if you are quite sure you are right, you know you hate losing. You can make this choice deliberatively. It is not rational or irrational to do so. Some preferences may be of course more appropriate according to the situation. If you are a medical doctor, loss aversion is required. You deal with lives. If you are a wealth manager, you should adapt to your client’s preferences. If you are a trader, neutrality may be effective if you want to maximize expected value. But this may be of course challenged by external constraints like corporate governance, bonus, or competition. To cut it short, loss aversion and greed are more a question of personal preferences, personality, or wisdom.

For probability distortion, the question is trickier. We do not really choose to overestimate small probabilities and underestimate large probabilities. This is not a question of preference and we cannot help it so easily. Are we irrational if we do so? Again, the answer is not straightforward. Yes we are, as we misperceive the reality. However, probability distortion can be useful in practice. If you are an entrepreneur, a bit of optimism can help inspire your team. The heuristics “If I am not sure, let’s say there is a 50% of chance” can be effective to make super-quick decisions.

What about memory, causality, or social biases? Is it irrational to generalize from our past experiences, to prefer to collaborate with people like us, to punish free riders even if it is costly…? Such biases often make sense from an evolutionary perspective. Using our past experiences helps us make decisions when we lack information. Trusting our kin and punishing free riders helps the tribe to survive.

Many cognitive biases are heuristics or intuitions which can be effective in making quick and result-oriented decisions in a complex and uncertain environment. But their solution is often approximate. When we have time and access to more information, a deliberative thought is often a better option.

The optimal strategy is expected value maximization….?

First, in the questionnaire, there may be many situations where two bets are different with the same Expected Value (EV). For instance, a bet where we have a 50% chance of losing $50 or winning $100 and a bet where we have 50% chance of winning $50 or nothing. The strategy of EV maximization can thus lead to different profiles. You can in this case decide to gamble with the lowest variance. But this may not be always optimal. In the case of a “winner takes all” competition for instance, where the sole objective is to achieve the highest performance, choosing the bet with the larger outcomes may be more relevant. On

Moreover, expected value strategy has raised many paradoxes like the “St Petersburg” paradox:

You are proposed the following deal:

“I will toss a coin until it hits heads. If the coin hits heads the first time, you earn 1$. If the coin hits heads on the second time, you earn 2$, on the third time you earn 4$, fourth time 8$…”

How much are you willing to pay to play this game?

Perhaps not so much. Imagine you get heads on the first times, you come back home with only $1 or $2… not a good deal.

However, the game can last for a long time. Hitting heads on the 10th toss would give you 1 024$, 1 048 576$ on the 20th toss. On the 38th toss, you would be by far the richest man on earth. And it could keep going on. The expectation for this gamble is infinite. Nevertheless, the gamble seems to be worth only a small amount of money.

How can I be neutral?

Neutrality reflects the fact that your perceptions of probabilities and values are not biased at all. Therefore, as a neutral agent, your perception of the value of a gamble is its expected value.

If you want to be risk neutral in our questionnaire, don’t even look at the full description of the gambles, focus on their expected values and always pick the highest one. If you face two gambles with the same Expected Value, choose one randomly.

However, if you follow this strategy, the questionnaire may not reveal absolute neutrality. Indeed, our algorithm starts from the principle that people are a priori biased based on previous empirical findings.

I did the questionnaire twice and I got different profiles…

Our investor profile is not fixed. For instance, empirical studies have shown that people are more risk-taking after losses, with a higher level of testosterone, when they are upset and even when the temperature is lower! (Cao et al., 2005). Don’t hesitate to take several times the questionnaire to discover how your personal profile evolves over time.

To go further :

Abdellaoui, M. H. (2013). Do Financial Professionals Behave According to Prospect Theory? An Experimental Study. Theory and Decision , 74, 411-429.

Ariely, Dan. (2010) Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions.

Cao, M., & Wei, J. (2005). Stock market returns: A note on temperature anomaly. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(6), 1559-1573.

Chen, M. K., Lakshminarayanan, V., & Santos, L. R. (2006). How basic are behavioral biases? Evidence from capuchin monkey trading behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 114(3), 517-537.

De Palma, André, et al. “Beware of black swans: Taking stock of the description–experience gap in decision under uncertainty.” Marketing Letters 25.3 (2014): 269-280.

Kahneman, & Tversky. (1992). Advances in prospect theory cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 297-323.

Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Kahneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision. Harvard business review, 89(6)

Levitt, Steven D., and Stephen J. Dubner. Freakonomics. Vol. 61. Sperling & Kupfer editori, 2010.

Taleb, N. (2007). The black swan: the impact of the highly improbable.

Taleb, N. (2005). Fooled by randomness: The hidden role of chance in life and in the markets

Taleb, N. (2012). Antifragility: Things that gain from disorder.

Richard H. Thaler, Cass R. Sunstein (2009), Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness

Caterina Lucarelli & Pierpaolo Uberti & Gianni Brighetti, 2015. “Misclassifications in financial risk tolerance,” Journal of Risk Research, Taylor & Francis Journals, vol. 18(4), pages 467-482, April.

Wakker, P. P. (2011). Prospect Theory: For Risk and Ambiguity.